|

Table of Contents

|

Pitfalls for New Believers

There are of course two major pitfalls: once you touch new souls and bring them into the Church, they either fall into the escapism of Byzantium liturgical aesthetics, which bears no real fruit and does not change lives in the modern situation; or they become satisfied with their lot as adopted foster-children, spinelessly assimilating themselves into a foreign family and allowing themselves to be drained of their initial enthusiasm and energy (p. 182)

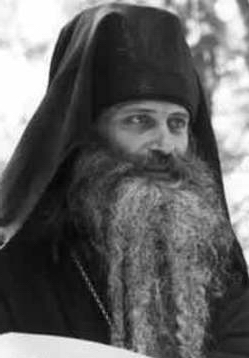

Archbishop John's Attraction was His Love

Archbishop John needed to give Eugene few instructions and explanations. Eugene internalized the spiritual image of the Archbishop, whom he perceived as a reflection of Christ Himself; and he was to carry this image throughout his life as a source of guidance. In later years, when he beheld this image most clearly after long experience as a Christian, he was to write: "If you ask anyone who knew Archbishop John what it was that drew people to him ? and still draws people who never knew him , the answer is always the same: he was overflowing with love; he sacrificed himself for his fellow men out of absolutely unselfish love for God and for them. This is why things were revealed to him which could not get through to other people and which he never could have known by natural means. He himself taught that, for all the 'mysticism' of out Orthodox Church that is found in the Lives of the Saints and the writings of the Holy Fathers, the truly Orthodox person always has both feet firmly on the ground, facing whatever situation is right in front of him. It is in accepting given situations, which require a loving heart, that one encounters God." (p.200)

Eugene's Reflection on His Early Orthodox Beliefs

Reflecting on his "lay sermons" years later, Eugene was to write: "I don't know who if anyone read them, and looking back on then now I find them, despite the 'feeling' I put into them, somewhat 'abstract,' the product of thinking that hadn't too much experience as yet either of Orthodox literature or Orthodox life. Still, for me they served an important function in my understanding and expression of various Orthodox questions and even in my Orthodox 'development,' and Vladika John 'pushed' that." (p. 266-267)

One's Personal Responsibility as an Orthodox Believer

Feeling their inadequacy and inexperience as editors of an Orthodox journal, however, the brothers wanted some kind of insurance against making errors. Knowing they could find no better safeguard than a living saint like Archbishop John, they asked him to carefully approve each issue before publication. They hoped this would also bring them into closer contact with him and thereby enhance their missionary endeavors. The outcome, however, was not what they expected.

When Gleb explained the contents of the first issue before printing it, Archbishop John approved without hesitation and emphatically said, "Print!" And when asked about subsequent issues, he approved before the brothers could even tell them what was in them!

Gleb was puzzled. Why didn't the Archbishop try to exercise the power of censorship, since the magazine was being published within his diocese? Gleb's consternation increased when, after the publication of the fifth issue, a reader became quite incensed at a certain article that Eugen had written. The article, in the "Orthodoxy in the Contemporary World" section, had been about Pope Paul IV's address before the United Nations, which we have recounted elsewhere. Expressing his indignation, the reader returned the issue with notes in the margins. Here was a magazine full of the treasures of the Orthodox Faith, and at the end of it one is faced with an article comparing the Pope to the Antichrist! Who did these "pipsqueak" editors think they were to make such outlandish statements about world-recognized spiritual leader?

Hurt by this bitter response, the brothers told Archbishop John what had happened. As Eugen looked on, Gleb asked the Archbishop, "Why didn't you check over this issue so we would have known before we printed it?!"

Having learned the contents of the article in question, the Archbishop looked keenly into Gleb's eye. "Didn't you attend the courses at the seminary?" he asked.

"Yes," Gleb said.

"And didn't you complete them?"

"Yes."

"Did you have Archbishop Averky as your instructor?"

"Yes.'

"And weren't you taught that in times of trouble, each Christian is himself responsible for the fullness of Christianity? That each member of the Orthodox Church is responsible for the whole Church? (emphasis mine) And that today the Church has enemies and is persecuted from outside and within?"

"Yes, I was," Gleb affirmed.

This, the Archbishop went on to tell the brothers, was why he deliberately did not censor their magazine. He wanted them to be responsible for what they printed; otherwise, they would not be following their own consciences, but just someone else's opinion. If they made mistakes, they would be the ones to answer for them before God, and would not be tempted to blame others. In times like these, he said, it is crucial for the preservation of Christianity that Orthodox workers be able to work for Christianity independently. It is praiseworthy when they do creative work waiting for instructions. (p. 281)

On Writing (Fr. Seraphim's counsel to articles written by Alexey)

"It is not at all 'vain and presumptuous' for you to write such an article, for if nothing else it helps you to clarify and develop your own ideas and feelings..." (p. 482)

Orthodoxy Alone

"Don't mix Orthodoxy with anything else. If you want Orthodoxy, go into it deeply; if not, leave it alone and don't take anything from it, not icons or Jesus Prayer or anything else." (p. 582)

Forcing Oneself in All Areas of Life

If a man forces himself only to prayer, that he may obtain the grace of prayer, but will not force himself to meekness and humility and love and the rest of the Lord's commandments... then, to the measure of his purpose and free will, sometimes a grace of prayer is given him, in part... but in character he is like what he was before. He has no meekness, because he did not seek it with pains... He has no humility, because he did not ask for it or force himself to it. He has no love towards all men, because he had no concern or striving about it in his asking for prayer; and in the accomplishment of his work he has no faith and trust in God, because he did not know himself, did not discover that he was without it, or take trouble with pain, seeking from the Lord to obtain from faith towards him and a real trust.

· St. Macarius the Great (p. 596)

The Needed Simplicity of Spirit

If a person doesn't react simply, naturally and freely, motivated by love for God and neighbor, he becomes hardened in his own way of spiritual life, which becomes just another form of self-satisfaction. He clings to his ?spiritual opinions?: about what private spiritual practices or podvigs he should take on, about how the church services should be conducted, how the canons should be followed, how his monastery or parish should be run, what it should spend its money on, what church-political "position" it should take, how the work should be done, how "truly spiritual" people should behave and carry themselves, etc. It is bad enough when such a person no longer hears God. But if this continues, something even worse happens: he begins to mistake his "spiritual opinion" for the voice of God. And then no one can tell him anything. (p. 597)

Having the Faith Entails Sharing it and not Dialoging About it

In later years, when Fr. Seraphim was asked about the Orthodox attitude toward non-Christian religions, he replied that each person is responsible for what he is given: "Once you accept the revelation [of the Gospel], then of course you are much more responsible than anyone else. A person who accepts the revelation of God come in the flesh and then does not live according to it, he is much worse off than any pagan priest or the like."

And yet, as Fr. Seraphim wrote in his book, "For the Christian who has been given God's Revelation, no 'dialogue' is possible with those outside the Faith. Be ye not unequally yoked with unbelievers... What communion hath light with darkness... or what part hath he that believeth with an infidel" (II Cor. 6:14-16) The Christian calling is rather to bring the light of Orthodox Christianity to them, even as St. Peter did to the God-fearing household of Cornelius the Centurion (Acts 10:38-48), in order to enlighten their darkness and join them to the chosen flock of Christ's Church.? (p. 641)

How to be Orthodox

This path, however, requires far more than just wearing robes, doing all the "right" monastic things, and thinking that thereby one is somehow "spiritual." "Unfortunately," Fr. Seraphim wrote, "the awareness of Orthodox monasticism and its ABC's remains largely, even now, an outward matter. There is still more talk of 'elders,' 'hesychasm,' and 'prelest' than fruitful monastic struggles themselves. Indeed, it is all too possible to accept all the outward marks of the purest and most exalted monastic tradition: absolute obedience to an elder, daily confession of thoughts, long church services or individual rule of Jesus Prayer and prostrations, frequent reception of Holy Communion, reading with understanding of the basic texts of spiritual life, and in doing all this to feel a deep psychological peace and ease ? and at the same time to remain spiritually immature. It is possible to cover over the untreated passions within one by means of a facade or technique of 'correct' spirituality, without having true love for Christ and one's brother. The rationalism and coldness of heart of modern man in general make this perhaps the most insidious of the temptations of the monastic aspirant today. Orthodox monastic forms, true enough, are being planted in the West; but what about the heart of monasticism and Orthodox Christianity: repentance, humility, love for Christ our God and unquenchable thirst for His Kingdom?"

Here is where the monasticism of ancient Gaul has much to teach the monks of these latter times. Newly born, wide-eyed and vibrant with its initial impulse, it rises above the smog of ?spiritual calculation? and soars in the pure mountain air of Gospel simplicity. As Fr. Seraphim put it, "it is always close to its roots and aware of its aim, never bogged down in the letter of its disciplines and forms. Its freshness and directness are a great source of great inspiration even today.

"Finally, Orthodox monastic Gaul reveals to us how close true monasticism is to the Gospel. St. Gregory's Life of the Fathers is particularly insistent on this point: each of the lives begins with the Gospel, and each saint's deeds flow from it as their source. No matter what he describes in Orthodox Gaul ? whether the painting of icons, the undertaking of ascetic labors, the veneration of a saint's relics ? all is done for the love of Christ, and this is never forgotten.

"The monastic life, indeed, even in our times of feeble faith, is still above all the love of Christ, the Christian life par excellence, experienced with more patient sufferings and much pain. Even today there are those who penetrate the secret of this paradise on earth ? more often through humble sufferings than through outward 'correctness' ? a paradise which worldly people can scarcely imagine." (p. 673-674)

Education for Hearts and Souls, Not Always Minds

For Fr. Seraphim, it was such a consolation to be able to transmit Orthodoxy to spiritually thirsty people that it mattered not how many there were or how "intelligent." His concern was not to create "experts"in Orthodoxy. He was less concerned with what people's minds did with what he taught as with what their hearts and souls did with it. Thus, although his own mind could grasp things faster than just about anyone else's, he was exceedingly patient with "slow learners" who yet struggled to understand. (p. 746)

Warning to those Young in Orthodoxy

In so many of our Orthodox people today (especially converts) one can see a frightful thing: much talk about the exalted truths and experiences of true Orthodoxy, but mixed with pride and a sense of one's own importance for being "in" on something which most people don't see. (p. 752)

Orthodox theology, of course, is much deeper and makes much better sense than the erroneous theologies of the modern West, but our basic attitude towards it must be one of humility and not pride. Converts who pride themselves on "knowing better" than Catholics and Protestants often end by "knowing better" than their own parish priest, bishop, and finally the Fathers and the whole Church! (p. 757)