|

Table of Contents

|

Eugene's Reflection on His Early Orthodox Beliefs

Reflecting on his "lay sermons" years later, Eugene was to write: "I don't know who if anyone read them, and looking back on then now I find them, despite the 'feeling' I put into them, somewhat 'abstract,' the product of thinking that hadn't too much experience as yet either of Orthodox literature or Orthodox life. Still, for me they served an important function in my understanding and expression of various Orthodox questions and even in my Orthodox 'development,' and Vladika John 'pushed' that." (p. 266-267)

Eugene's Discernment of the Time Demonstrated

Helen Kontzevitch praised the magazine for what she called its presentation of Orthodoxy: the fact that it did not just include a hodgepodge of unrelated material which happened to be at hand, but that it carefully presented related material in a traditional context which was at the same time accessible to contemporary readers. The brothers achieved this through a blending of ancient and modern materials (including their own writings), through explanatory notes and prefaces, and not least through lots of pictures. (p. 280)

Eugene's Awareness of Nature's Transience Despite His Closeness

One may well wonder at this man, while being cautious about making an idol of nature, had a greater appreciation and fascination for it than the vast majority of people. But it is not true that those who love life the best are those who have been closest to its absence? A small child, having come so soon from non-being, rejoices innocently in existence. As he grows older he becomes more jaded, and it is only through a period of serious illness or the death of a loved one that he comes again to see the preciousness of the life he took for granted. So too with Eugene. Profoundly seeing the transience of the created order, he was able to know it as it truly was and thus love it better ? for love is the highest knowledge. (p. 372)

The Influence of the Wilderness by Living in the Wilderness

"Our attention," Fr. Herman writes, "gradually began to take in the life that directly surrounded us. We began to see reality as it is and not depend on human opinion. The sound of the wind, the changes of the weather, its influence on one's mood, the life of the forest animals and birds, it was as if even the breathing of the plants and trees now had significance. Peaceful ideas were sown. The eyes began to accustom themselves to seeing not just what was external and jumped out at them, but the essence of the matter. Although friends came with love and tried to help, they were actually more of a burden and right from the beginning made errors of simple judgment, worrying about the external aspect that passes and not seeing the essence. And with what joy was the heart filled when silence reigned again and much-speaking stillness." (p. 444)

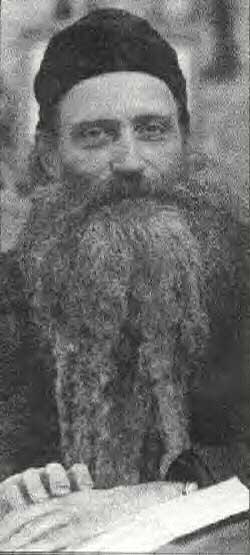

Personal Note about Fr. Seraphim

As the golden glow of the morning light filtered through the broad canopy of oak leaves, Fr. Seraphim could be seen blessing and even kissing the trees. (p. 445)

Fr. Seraphims Readings - "Confessions"

Every year during Great Lent, Fr. Seraphim tried to reread the whole of Blessed Augustine's Confessions, and every year he would weep at Augustine's profound repentance. From the portions he underlined in the book, it is clear that Fr. Seraphim saw his own life in the story of Blessed Augustine's conversion from rebellion to faith. In many passages the similarities are striking, as if it were Fr. Seraphim and not Augustine who was writing about his past. (p. 447)

On Hesychasm

Observing Fr. Seraphim's silent contemplation, Fr. Herman would tell him half-joking, "You're a hesychast!"- meaning a "silent one" engaged in direct contemplation of Divinity. Fr. Seraphim, however, did not like this term applied to himself. He even became indignant, saying, "I don't know what that means." Of course he knew intellectually, but he did not want to pretend to understand it from experience. He detested posing and fakery of any kind. For him, spiritual life had to be first of all down to earth, filled with humility and sober awareness of one's low spiritual state. In his younger days he had written: "He who thinks himself self-sufficient is in the snare of the devil; such a man who thinks further that he is 'spiritual,' has become almost an active accomplice of the devil, whether he realizes it or not." (p. 449)

The Jesus Prayer in Platina

Outside the Church services, Fr. Seraphim would strive to remember God by saying the Jesus Prayer throughout the day, whether while working, resting, or taking a walk. The brothers were reminded to do likewise. From the very beginning of the skete's existence, Fathers Serphim and Herman had instituted the traditional monastic practice of saying the Jesus Prayer aloud whenever entering a room. This practice had been followed by the monks on ancient times in order to foil the tricks of the demons, who were know to enter the cells of desert-dwellers without warning. (p. 574)

Fr. Seraphim's "Normal" Life

Fr. Seraphim was not like his preceptor Archbishop John in taking on a superhuman battle against the basic requirements of eating and sleeping. Whereas Archbishop John usually ate only once a day, at midnight, Fr. Seraphim ate two or three meals a day along with the rest of the brothers. And while Archbishop John slept only an hour or two a night without ever lying down, Fr. Serphim usually slept a normal amount in a normal fashion ? although he sometimes stayed up late in prayer. (p. 603)

Fr. Seraphim and the Jesus Prayer

When at times he had to wait for something, such as for the meal to end in the refectory, he would be seen with bowed head, saying the Jesus Prayer mentally with his prayer rope. (p. 604)

Fr. Seraphim and Music

We have seen how, during his monastic years, Fr. Seraphim did not seek to enjoy music in and of itself. For him, music was but a means to lead one to prayer. He accepted music only as a ?part of the whole? which had been created to glorify God.

Since both Platina fathers had to some degree been converted through the music of great Christian composers, Fr. Herman was intrigued by the "excessive ascetic caution," as he called it, with which Fr. Seraphim had come to approach music. (932)